An Evidentiary Hearing was held last June, with more filings since then. The Hearing Officer's report held that the complaint against the project should not be upheld. However it also recommended that the PUC examine whether such Feed in Tarrif projects are in the Public Interest. The Ocean View plan is an FIT project.

Feed In Tariff (FIT) was adopted by the PUC in 2008 as an incentive to develop renewable energy projects in Hawai'i. It gave an incentive for owners of new alternative energy sources to receive 23.8c per kWh, a much higher rate than paid today. FIT was intended to encourage owners of agricultural land, like ranchers and farmers, to install facilities and sell the power to the utility.

The company SPI took the approach of buying up houselots, zoned agriculture, in a residential town of Ocean View in order to cover them with solar panels. Complainants call it a misuse of the program and an effort to industrialize a place where people live.

In the filings, PUC Hearings Officer Mike Wallerstein wrote, "The Commission directed me to consider evidence whether the FIT Projects are 'closer in concept' to individual projects or to a larger consolidated project and whether the Competitive Bidding Framework would allow the FIT Projects to be considered in the aggregate". Wallerstein recommended that "the commission definitively determine whether the FIT Projects are in the public interest with the benefit of the evidence now in the record."

Attorneys for SPI, which currently owned by a Chinese solar developer that plans to locate 17 solar farms on three-acre houselots in Ocean View, argued that the project should not be judged as to whether it is a public benefit. They said, "Commission action could potentially lead to invalidating the solar projects in question."

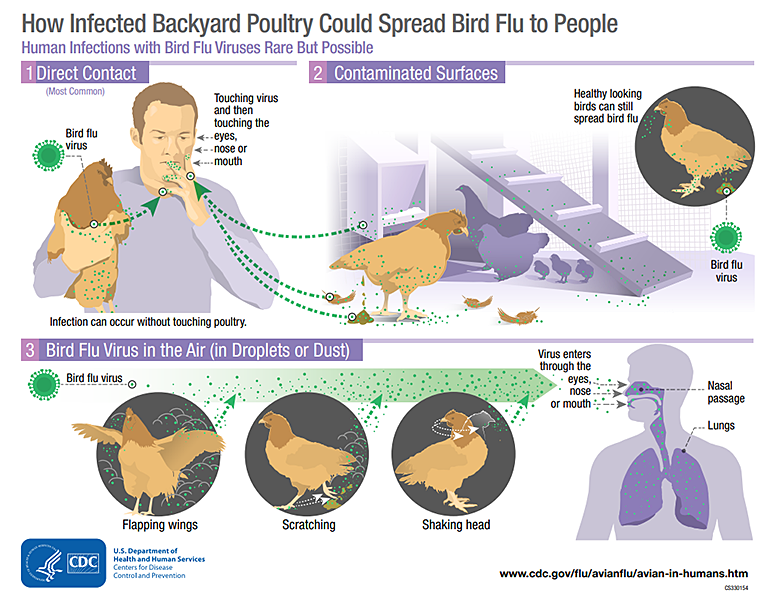

The state Department of Health states that bird flu is a public health concern in Hawai'i because, "Influenza viruses undergo genetic reassortment, or change, as they spread between different animal species and humans. There is a risk that the H5N1 or other avian influenza viruses might change to spread more easily among humans, potentially leading to a pandemic. Therefore, it's extremely important to adopt avian influenza prevention practices, monitor for animal and human infections and detect the development of any person-to-person spread as early as possible."

Participation in the National Poultry Improvement Plan with routine sampling of chickens at the state's largest poultry farm;

Participation in U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) collection and testing of wild bird specimens;

Testing of any lactating cows being brought into the state;

Working with federal, state and county agencies to provide updated information to the public in a timely manner.

Feed In Tariff (FIT) was adopted by the PUC in 2008 as an incentive to develop renewable energy projects in Hawai'i. It gave an incentive for owners of new alternative energy sources to receive 23.8c per kWh, a much higher rate than paid today. FIT was intended to encourage owners of agricultural land, like ranchers and farmers, to install facilities and sell the power to the utility.

|

| A neighborhood in Ocean View where industrial solar is still planned and would cover three acres lots in the residential community where land is zoned agriculture. Photo by Annie Bosted |

The company SPI took the approach of buying up houselots, zoned agriculture, in a residential town of Ocean View in order to cover them with solar panels. Complainants call it a misuse of the program and an effort to industrialize a place where people live.

In the filings, PUC Hearings Officer Mike Wallerstein wrote, "The Commission directed me to consider evidence whether the FIT Projects are 'closer in concept' to individual projects or to a larger consolidated project and whether the Competitive Bidding Framework would allow the FIT Projects to be considered in the aggregate". Wallerstein recommended that "the commission definitively determine whether the FIT Projects are in the public interest with the benefit of the evidence now in the record."

Attorneys for SPI, which currently owned by a Chinese solar developer that plans to locate 17 solar farms on three-acre houselots in Ocean View, argued that the project should not be judged as to whether it is a public benefit. They said, "Commission action could potentially lead to invalidating the solar projects in question."

They wrote, "If the Commission agreed with the Complainants/Consumer Advocate, then the Commission would conduct a public interest analysis to consider if the projects (aggregately) in a way that would make them potentially violate the FIT tariffs and the Competitive Bidding Framework. That would be essentially be a write in of new rules for the FIT Projects that are not – and have never been – included

or addressed in the FIT tariffs."

They also stated, "Complainants filed this Complaint and initiated this proceeding in August of 2016. Now, more than eight years later this matter still remains unresolved. The Intervenors' multi-million dollar investment to date, in order to keep these projects alive, still faces regulatory uncertainty."

Ranchos residents who filed the original complaint against the utility (then HECO and HELCO and now Hawaiian Industries) vehemently sided with the Hearings Officer, arguing that the project should be judged whether it is a public benefit. They presented a long list of "public benefit" points for the Commission to consider. They argued that if Ocean View was to be industrialized with power-producing facilities, it could become the victim of a deadly fire similar to Lahina's that was caused by a faulty transmission line. They argued that the project is unpopular and will reduce the value of homes in an economically challenged community. Without battery backup, the project can only produce power during daylight hours and not when it is most needed, said the complainants.

The Complainants wrote, "The FIT Program requires the utility to purchase power from the FIT Project owner at the rate of 23.8c per kWh for 20 years. Today, new solar projects are competitively negotiated. Accordingly, PV projects with battery backup are selling renewable power to HELCO for about 9c per kWh."

"We, the Complainants, note that although the Intervenors rigorously argue against the proposal to recommend that the Commission evaluate the Ocean View project, at no time do they argue that the project is, in fact, in the public interest.

"Finally, while not evidentiary, we would conclude with a popular, commonsense adage: If it looks like a duck, and it walks like a duck, and it quacks like a duck, it is a duck!".

Attorneys for Hawaiian Electric sided with SPI's attorneys and argued that the Commission should not "definitively determine whether the FIT Projects are in the public interest."

AN AVIAN INFLUENZA OUTBREAK IS A CONCERN OF STATE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. The agency sent out a document to help educate the public about the H5N1 disease and its possible risks to humans. On the mainland bird flu has wiped out many populations of turkeys, broiler chickens and egg-laying hens, causing the price of eggs, chicken and turkeys to go up. Even Thanksgiving is effected. Turkey production was the lowest in 2024 since 1985 with farmers raising 205 million this year, down 6% from last year.

or addressed in the FIT tariffs."

They also stated, "Complainants filed this Complaint and initiated this proceeding in August of 2016. Now, more than eight years later this matter still remains unresolved. The Intervenors' multi-million dollar investment to date, in order to keep these projects alive, still faces regulatory uncertainty."

|

| A newswire photo regarding SPI joining Nasdaq in 2016. |

The Complainants wrote, "The FIT Program requires the utility to purchase power from the FIT Project owner at the rate of 23.8c per kWh for 20 years. Today, new solar projects are competitively negotiated. Accordingly, PV projects with battery backup are selling renewable power to HELCO for about 9c per kWh."

"We, the Complainants, note that although the Intervenors rigorously argue against the proposal to recommend that the Commission evaluate the Ocean View project, at no time do they argue that the project is, in fact, in the public interest.

"Finally, while not evidentiary, we would conclude with a popular, commonsense adage: If it looks like a duck, and it walks like a duck, and it quacks like a duck, it is a duck!".

Attorneys for Hawaiian Electric sided with SPI's attorneys and argued that the Commission should not "definitively determine whether the FIT Projects are in the public interest."

To read comments, add your own, and like this story, see facebook.com/kaucalendar. See upcoming events, print edition and archive at kaunews.com.

AN AVIAN INFLUENZA OUTBREAK IS A CONCERN OF STATE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. The agency sent out a document to help educate the public about the H5N1 disease and its possible risks to humans. On the mainland bird flu has wiped out many populations of turkeys, broiler chickens and egg-laying hens, causing the price of eggs, chicken and turkeys to go up. Even Thanksgiving is effected. Turkey production was the lowest in 2024 since 1985 with farmers raising 205 million this year, down 6% from last year.

|

The state Department of Health states that bird flu is a public health concern in Hawai'i because, "Influenza viruses undergo genetic reassortment, or change, as they spread between different animal species and humans. There is a risk that the H5N1 or other avian influenza viruses might change to spread more easily among humans, potentially leading to a pandemic. Therefore, it's extremely important to adopt avian influenza prevention practices, monitor for animal and human infections and detect the development of any person-to-person spread as early as possible."

DOH also states that H5N1, even in its current form, can impact agricultural operations. For poultry farms, when infected birds are found, the whole flock needs to be culled to contain the infection and keep it from spreading to other birds. These measures are of course incredibly disruptive to farm operations and livelihood.

According to DOH, "It is important to protect people who work closely with animals that are susceptible to infection, such as poultry farm workers. These are the people at highest risk of getting infected. DOH, HDOA and USDA have been working closely together over the past few months to plan for such a scenario. HDOA also is working with the University of Hawai'i College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resilience to assist in outreach to poultry farms."

The Health Department's presentation to the public also includes the following:

According to DOH, "It is important to protect people who work closely with animals that are susceptible to infection, such as poultry farm workers. These are the people at highest risk of getting infected. DOH, HDOA and USDA have been working closely together over the past few months to plan for such a scenario. HDOA also is working with the University of Hawai'i College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resilience to assist in outreach to poultry farms."

The Health Department's presentation to the public also includes the following:

Is it safe to eat eggs from local farms? Yes. There have been no reports of sick birds on any commercial farm in Hawaiʻi. The likelihood that eggs from infected poultry are found in the retail market is low and proper storage and preparation reduce further risk.

Do we need to get rid of all those feral chickens? At this point, the best defense against the avian flu is to avoid interacting with feral chickens and wild birds as much as possible. Generally, if the chickens appear healthy and are behaving normally, the risk is probably lower. However, if you find several dead or dying birds in a particular area, please report it as soon as possible to DOH and HDOA. From a medical perspective, it is not clear that a mass culling of feral chickens would appreciably reduce the risk to humans.

|

| Hawaii Department of Agriculture received confirmation from U.S. Department of Agriculture's National Veterinary Services Laboratories that highly pathogenic avian influenza was detected in a backyard flock of various birds in Central Oʻahu. The birds were destroyed. |

Do we need to get rid of all those feral chickens? At this point, the best defense against the avian flu is to avoid interacting with feral chickens and wild birds as much as possible. Generally, if the chickens appear healthy and are behaving normally, the risk is probably lower. However, if you find several dead or dying birds in a particular area, please report it as soon as possible to DOH and HDOA. From a medical perspective, it is not clear that a mass culling of feral chickens would appreciably reduce the risk to humans.

Should I remove or turn in dead or sick birds? To remove a dead wild bird on property, wear disposable gloves or turn a plastic bag inside out and use it to pick up the carcass. Double-bag the carcass and throw it out with the regular trash. Wash hands and disinfect clothing and shoes after handling a dead wild bird. Be mindful of any health symptoms that may develop afterward. For more information, visit: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/fs-hpai-dead-wild-bird.508.pdf

What is "bird flu"? Avian influenza (bird flu) viruses occur naturally in wild birds. Avian influenza A viruses have been isolated from more than 100 different species of wild birds around the world, including ducks, geese, terns, plovers and sandpipers. These viruses are very contagious among birds and have the potential to cause severe illness among poultry, other animal species and even among humans exposed to the virus. It has the potential to affect common Hawai'i backyard birds like mynah, bulbuls and zebra doves.

Am I at risk from H5N1? Although the health risk from bird flu viruses is low, the following may place individuals at increased risk of infection: Unprotected close or direct contact with sick or dead animals, including wild birds, poultry, other domesticated birds and other wild or domesticated animals.

Handling the feces, bedding (litter), or materials that have been touched by, or close to, birds or other animals on a farm with suspected or confirmed H5N1 infection.

Consuming raw, unpasteurized milk or other dairy products.

How do I know I've been infected? Symptoms of avian influenza in humans usually develop within two to five days of exposure but can take up to 10 days to develop in some cases. Symptoms that are associated with bird flu infection in humans are typically mild and may include fever, cough, sore throat or conjunctivitis ("pink eye"). Avian influenza in humans can be treated with antiviral drugs, prescribed by health care providers.

Those with symptoms and a known exposure within the past ten days should contact a primary care provider for evaluation and testing. Also contact the DOH Disease Reporting Line at 808-586-4586 for further guidance (calls answered 24/7). Also, call if experienced symptoms that have since been resolved. Health care providers can submit specimen samples to Hawaiʻi's State Laboratory Division (SLD) for bird flu testing.

What if I have become infected with bird flu? It is recommended that infected individuals should stay at home and away from others, including household members, except for when seeking medical evaluation. If need to leave home or are not able to fully isolate from others, wear a mask and increase hand hygiene (soap and water for at least 20 seconds) to prevent the spread of the virus.

What is "bird flu"? Avian influenza (bird flu) viruses occur naturally in wild birds. Avian influenza A viruses have been isolated from more than 100 different species of wild birds around the world, including ducks, geese, terns, plovers and sandpipers. These viruses are very contagious among birds and have the potential to cause severe illness among poultry, other animal species and even among humans exposed to the virus. It has the potential to affect common Hawai'i backyard birds like mynah, bulbuls and zebra doves.

Am I at risk from H5N1? Although the health risk from bird flu viruses is low, the following may place individuals at increased risk of infection: Unprotected close or direct contact with sick or dead animals, including wild birds, poultry, other domesticated birds and other wild or domesticated animals.

Handling the feces, bedding (litter), or materials that have been touched by, or close to, birds or other animals on a farm with suspected or confirmed H5N1 infection.

Consuming raw, unpasteurized milk or other dairy products.

How do I know I've been infected? Symptoms of avian influenza in humans usually develop within two to five days of exposure but can take up to 10 days to develop in some cases. Symptoms that are associated with bird flu infection in humans are typically mild and may include fever, cough, sore throat or conjunctivitis ("pink eye"). Avian influenza in humans can be treated with antiviral drugs, prescribed by health care providers.

Those with symptoms and a known exposure within the past ten days should contact a primary care provider for evaluation and testing. Also contact the DOH Disease Reporting Line at 808-586-4586 for further guidance (calls answered 24/7). Also, call if experienced symptoms that have since been resolved. Health care providers can submit specimen samples to Hawaiʻi's State Laboratory Division (SLD) for bird flu testing.

What if I have become infected with bird flu? It is recommended that infected individuals should stay at home and away from others, including household members, except for when seeking medical evaluation. If need to leave home or are not able to fully isolate from others, wear a mask and increase hand hygiene (soap and water for at least 20 seconds) to prevent the spread of the virus.

Treatment for bird flu infections in humans is available. A health care provider might prescribe an antiviral medication used for treatment of seasonal flu. These drugs can also be used to treat an avian influenza virus infection. It is important to start antiviral treatment as soon as possible and to follow the directions for taking all of the medication that is prescribed.

Is there an H5N1 vaccine for humans? The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has done the preliminary scientific work that would enable it to produce vaccines, if needed, to protect against the strain of avian flu currently circulating on the U.S. mainland (clade 2.3.4.4b). However, there is no vaccine currently in production. Regular seasonal flu vaccines do not provide protection against avian influenza A viruses, but getting the seasonal flu vaccine lowers the chance of a person becoming infected with seasonal flu and H5N1 at the same time. That's important because it makes it harder for the virus to undergo reassortment, which could make avian flu better adapted to spread in people.

What is the risk right now? For the moment, the risk to the general public remains low. There have been a small number of human cases reported in the continental U.S., mostly among people working closely with infected animals. Human illnesses in the U.S. have been mild and self-resolving, primarily conjunctivitis or mild respiratory symptoms.

Is there an H5N1 vaccine for humans? The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has done the preliminary scientific work that would enable it to produce vaccines, if needed, to protect against the strain of avian flu currently circulating on the U.S. mainland (clade 2.3.4.4b). However, there is no vaccine currently in production. Regular seasonal flu vaccines do not provide protection against avian influenza A viruses, but getting the seasonal flu vaccine lowers the chance of a person becoming infected with seasonal flu and H5N1 at the same time. That's important because it makes it harder for the virus to undergo reassortment, which could make avian flu better adapted to spread in people.

What is the risk right now? For the moment, the risk to the general public remains low. There have been a small number of human cases reported in the continental U.S., mostly among people working closely with infected animals. Human illnesses in the U.S. have been mild and self-resolving, primarily conjunctivitis or mild respiratory symptoms.

What is DOH doing to protect the general public? DOH, in partnership with HDOA, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), is reinforcing longstanding efforts to detect avian influenza disease in birds, cattle and humans in Hawaiʻi. This includes:

Monitoring wastewater, human influenza infections detected in the laboratory, and emergency department visits for influenza as tracked on the Hawaiʻi Respiratory Disease Activity Summary dashboard;Participation in the National Poultry Improvement Plan with routine sampling of chickens at the state's largest poultry farm;

Participation in U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) collection and testing of wild bird specimens;

Testing of any lactating cows being brought into the state;

Working with federal, state and county agencies to provide updated information to the public in a timely manner.

Has there been any detection in any other wastewater treatment plant in Hawaiʻi? Other than the Wahiawā plant, there have been no detections reported to DOH as of Nov. 25, 2024.;

How did this begin? DOH first received a report of H5 detection in wastewater from the municipal Wahiawā wastewater treatment plant on O'ahu on Nov. 12, 2024. The positive sample had been collected on Nov. 7, and was tested as part of routine wastewater testing conducted by CDCʻs National Wastewater Surveillance System. The detection was made in wastewater as it exited the sewer pipes and before being treated at the wastewater treatment facility. The methods used for routine wastewater testing can only detect one part of the influenza virus, the H5 antigen. The test tells us that H5 influenza is present in the wastewater, but cannot tell us whether the virus detected was H5N1, specifically.See: https://health.hawaii.gov/docd/disease_listing/avian-influenza/

|

To read comments, add your own, and like this story, see facebook.com/kaucalendar. See upcoming events, print edition and archive at kaunews.com.

.JPG)

.png)

.JPG)

.gif)

.jpg)

.jpg)